Will they never return? Can this be considered another wave of emigration? Demographers Mikhail Denisenko and Yulia Florinskaya explain for the site https://meduza.io/.

After February 24, when Russia launched a full-scale war in Ukraine, many Russians decided to leave the country. For some, this is a temporary solution. Others realize that they may never return to the country. About how many people have left Russia, which of them can be officially considered emigrants, and how all this will affect the country in the future, Meduza spoke with Mikhail Denisenko, director of the HSE Institute of Demography, and Yulia Florinskaya, a leading researcher at the RANEPA Institute for Social Analysis and Forecasting .

The interview with Mikhail Denisenko took place before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, with Yulia Florinskaya after the start of the war.

– Can you already estimate how many people left Russia after February 24?

Julia Florinskaya: I don’t have any estimates – neither accurate nor inaccurate. It’s more of an order of numbers. My order of numbers is about 150 thousand people.

Why do I say so? All are based on approximately the same figures that were named. The number of departures from Russia to Georgia for the first week [of the war] was 25,000. There was a figure of 30-50 thousand who left for Armenia [from the end of February to the beginning of April]. About 15 thousand, according to the latest data, entered Israel. Based on these figures – since the circle of countries where people left is small – I think that in the first two weeks there were 100,000 people who left. Maybe by the end of March – beginning of April, 150 thousand, including those who were already abroad [at the time the invasion began] and did not return.

Now they are trying to estimate some millions, 500, 300 thousand. I don’t think in those categories – and the way these estimates are made seems questionable to me. For example, a survey conducted by [OK Russians project] Mitya Aleshkovsky: they just took these numbers – 25 thousand went to Georgia in the first week – and decided that in the second week there were also 25 thousand. And since 15% of those interviewed were from Georgia, they counted and said: it means that 300,000 left [from Russia].

But this is not done, because if you have 25 thousand in the first week, no one said that it will be the same in the second. Secondly, if 15% from Georgia answered you, this does not mean that there really are 15% of all those who left Russia during this time. All this is written with a pitchfork on the water.

– The other day, data appeared on the website of state statistics on the crossing of the border by Russians in the first three months of 2022. Do they not give an idea of the number of those who left?

Florinskaya: This data does not show anything. This is simply leaving the country (without data on the number of those who entered Russia back – approx. Meduza) – and for the quarter, that is, including the New Year holidays.

For example, 20,000 more people left for Armenia than in 2020 (before COVID [in Russia]), or 30,000 more than in 2019. To Turkey – in fact, the same number as in 2019. But in 2021, there were 100,000 more [those going there], since all other countries were closed.

In total, 3.9 million people left Russia in the first quarter of 2022, 8.4 million in 2019, and 7.6 million in 2020. Only in 2021, at the height of covid, there were fewer — 2.7 million. But this is logical.

– And when will the exact data on those who have left appear?

Florinskaya: Maybe there will still be some estimates, as Georgia gave on crossing its border (for example, at the end of March, the Georgian Ministry of Internal Affairs reported that 35 thousand citizens of the Russian Federation entered the country in a month, 20.7 thousand left; not reported). But official statistics will not appear this year.

Again, this is a border crossing. This does not mean that people are left. Among those who entered Georgia, there are those who first entered Armenia or, for example, Turkey.

– According to UN estimates, as of 2021, about 11 million immigrants from Russia lived abroad – this is the third figure in the world after India and Mexico. How correct are these data?

Mikhail Denisenko: When we talk about any social phenomenon, statistics must be understood. There are our statistics on migration, there are foreign ones, there are international organizations. When we use numbers and do not know the definitions, this leads to all sorts of incidents.

What are UN assessments? How are international migrants generally defined? A migrant is a person who was born in one country and lives in another (such migration is sometimes called lifelong migration). And the UN statistics are just based on this – they are about people who were born in Russia, but live outside of it.

What in these statistics does not suit me and many experts? Lifelong migration [according to the UN] also includes those who left Russia [for allied countries] during the Soviet period. Therefore, these figures [about emigrants from Russia], as well as the reverse ones (that 12 million migrants live in Russia), must be treated with care. Because there really are people… For example, I was not born in Russia. And in these statistics, I fall into the number of migrants. Nobody cares that I have been living in Russia since I was six years old, and my parents just worked abroad [RF].

Therefore, the figure of 11 million is dangerous. It creates the illusion that a large number of people have emigrated recently.

My colleagues and I have a book entitled “Migrations from the Newly Independent States. 25 years since the collapse of the Soviet Union. According to our estimates, from the late 1980s to 2017 inclusive, there are about three million people who were born in Russia and live in far abroad countries. That is, not 11 million [as in the UN data], but three. So, if you use UN statistics, you should, if possible, remove the former Soviet republics from it. That will be more correct. For example, many people were born in Russia and moved to Ukraine during the Soviet era. Or take the “punished” peoples: Latvians and Lithuanians returned from exile with children who were born in Russia.

– Where do they get data for compiling statistics on emigration?

Denisenko: There are two concepts in migration statistics: migration flow and migration stock, i.e. flow and number.

UN statistics are just numbers. A census is being carried out, in which there is a question about the place of birth. Further, the UN collects data from all countries where censuses were conducted and makes its own estimates. In countries where there is no census (these are poor countries or, say, North Korea), there are no migrants either. [In the census] there may be other questions: “When did you come to the country?” and “From what country?” They refine information about emigrants and, in principle, give us an idea of the flows.

Nationally representative surveys are also conducted. I will often appeal to the United States, because, from my point of view, migration statistics are well organized there. The American community survey is conducted there every year – and from these data I can get information, say, about how many immigrants from Russia are in the country.

Flow information can be obtained from administrative sources. We have this border service (it gives information about crossing the border, where you are going and for what reason) and the migration service (it collects information about those who came, from which country, at what age).

But you yourself understand what flow statistics are: the same person can travel several times during the year, and the information is collected not about people, but about movements.

Florinskaya: In Russia, [emigrants] are counted by the number of those who left [from among permanent residents]. At the same time, Rosstat considers only those who have been deregistered. And far from all Russians who emigrate are removed from this register. Just like not everyone who leaves the country are emigrants. Therefore, the first step is to identify [in the Rosstat data] Russian citizens who are deregistered and leave for Western countries (where emigration mainly goes), and count their number. Before covid, there were 15-17 thousand of them a year.

However, the majority leave without announcing their departure in any way, so it is customary to count according to the data of the host countries. They are several times different from the Rosstat data. The difference depends on the country, in some years [data of the host country] were three, five and even 20 times greater than the data of Rosstat [on leaving to this country]. On average, you can multiply by five or six figures [Rosstat about 15-17 thousand emigrants per year].

Earlier in Russia, emigrants were considered differently.

BUT AS?

Denisenko: There is a sacred principle in migration studies that it is better to study migration according to the statistics of countries and regions of reception. We need proof that the person left or arrived. Evidence that he left is often not there. You understand: a person leaves Moscow for the United States, receives a green card, and in Moscow he has a house, even a job. And [Russian] statistics do not see this. But in the United States (and other countries), he needs to get registered. Therefore, the reception statistics are more accurate.

And here another problem arises: who can be called a migrant? Any person who came? And if not anyone, then who? In the States, for example, you received a green card – you are a migrant. The same is true in Australia and Canada. In Europe, if you receive a residence permit for a certain period, preferably a long one (the same nine or 12 months), you have the status of a migrant.

In Russia, the system is similar to the European one. We use a temporary criterion: if a person comes to Russia for nine months or more, he falls into the so-called permanent population. And often this number [nine months] is identified with migration, although a person can come for two years and then go back.

Florinskaya: If we take the data of consular records in foreign countries of “classic” emigration, then at the end of 2021, about one and a half million Russian citizens were registered with consular records. As a rule, not everyone gets on the consular register. But, on the other hand, not everyone is filmed when they go back [to Russia].

You can also look at how many people have notified [Russian law enforcement] of a second citizenship or residence permit since 2014, when it was made mandatory. About a million people from the countries of classical emigration [from Russia] declared themselves over the years. But there are those who left earlier, of course, they did not declare anything.

How and where do they leave Russia

– Is it clear how Russia reached the indicator of three million people who left (according to your estimates)?

Denisenko: Yes, we know when people started leaving, where they left and for what reasons. The statistics speak for it.

You remember, in the Soviet Union, migration was not all clear. Until the end of the 1920s, the USSR was open, then closed. After the war, there was a small “window”, even a “window”, to Germany for a couple of years, then it slammed shut. With Israel, everything was quite difficult. But, as a rule, meetings [of Soviet leaders] with American presidents led to the fact that a “window” was opened to Israel, no, no, and thirty thousand [left]. In the 1980s, when the Afghan crisis began, migration [from the USSR] practically stopped.

Mikhail Sergeevich Gorbachev, who is often criticized, opened not a window, but really a window. Soviet legislation became more loyal – at least [to the departure of] certain peoples. Since 1987, the outflow began. At first, the window was open to ethnic migrants – Jews, Germans, Greeks, Hungarians, Armenians. At first, the outflow was small, but then it began to increase sharply.

The crisis of the 1990s, of course, began to push people out. Of the more than three million [emigrants], more than half left in the late 1980s-1990s. Almost 95% – to Germany, the United States and Israel. For a significant part of the people who left for Germany and Israel, the channel of emigration was repatriation. In the United States, the main channel then was refugees.

Then there was a turning point, and these repatriation resources were reduced [since most of the representatives of national minorities left]. In Germany, they began to limit the influx of repatriates. If at the beginning of the 1990s 75% [of those entering from Russia] were Germans, by the mid-1990s only 25% of them were Germans. And the rest – members of their families – were Russians, Kazakhs, anyone, but not Germans. Naturally, [this could lead to] problems with integration, with the language – and restrictions began to be introduced [for those wishing to leave], primarily in the German language. Not everyone could pass it: after all, German is not English.

In the 1990s, the biggest difficulty in leaving, I think, was standing in line at the embassy. There were still few consulates, it was necessary to stand for a very long time – not a day or two, but a week or two. But the countries were open enough [to accept people from the former USSR]. Everyone knew that there was a flow of mostly qualified people from the Soviet Union. There were really many different kinds of programs, grants – for students, scientists.

And in the early 2000s, all these privileges were closed. The country [Russia] became democratic [compared to the USSR], and, say, the status of a refugee had to be seriously proved, to compete with others who wanted to leave. On the one hand, the flow has decreased, selection systems have appeared. On the other hand, these selection systems, in fact, began to shape the flow of migrants: who leaves, why and where.

What did we end up with? Earned the channel “relatives”. Now 40-50% of migrants from Russia leave through the channel of family reunification, that is, moving to relatives.

Another category is highly qualified specialists: scientists, engineers, programmers, athletes, ballet dancers, and so on. In the 1990s, prominent people left [Russia], in the 2000s and 2010s, as a rule, young talented people. Another, third, category is wealthy people. For example, Spain was one of the first countries in Europe to allow the sale of real estate to foreigners. We have huge communities there.

What is called a wave of emigration? What waves of emigration from Russia are distinguished?

Denisenko: Imagine a graph in which the lower axis, the abscissa, is time. We [in Russia] have statistics on emigration in 1828, now 2022. And on this chart we plot the number of migrants. When the number increases, a kind of wave is formed. Actually, this is what we call a wave. Waves are something fundamental that lasts more than one year.

We actually had several such rises. The first wave – the end of the 1890s – the beginning of the century. This is Jewish-Polish migration, so it is usually not singled out as a wave. But it was a powerful wave, the most massive [emigration in the history of the country], we fought with the Italians for the first place in the number of emigrants to the United States. Then this wave began to be fueled by Russian and Ukrainian migrants. The First World War ended all this.

The second wave in chronology and the first, if we take the Soviet period, is white emigration. Then the military and post-war emigration in the 1940s-1950s. The migration of the period 1960-1980 is also sometimes called a wave, although this is incorrect. [On the chart] it’s a straight line, but from time to time there are bursts, stages. But the 1990s were a wave.

— And what happened to emigration from Russia in the last 20 years?

Denisenko: Were there any stages? It’s a good question, but it’s hard for me to answer it, because I don’t see any clear stages [during this period].

— According to my feelings, many politicians, activists and journalists began to leave the country in 2021. What does the statistics say about this?

Denisenko: I will disappoint you, but the statistics do not see this. But she may not see for various reasons.

Statistics, on the contrary, sees a reduction in flows – not only from Russia. Of course, covid, restrictive measures were taken [on movement between countries]. For example, American statistics – the United States occupies one of the top three places in the direction of emigration from Russia – for 2020 shows a halving in the number of entries. Except for those traveling on work visas. If we take the recipients of green cards, then there are also slightly fewer of them. The fact is that you apply for a green card a year or two [before moving]. The situation is similar in Europe: the reduction occurred almost everywhere, except for one category – those who go to work.

– You said that statistics do not see an increase in departures from Russia in 2021. As far as I know, many left for the same Georgia, where one can stay up to a year without a visa and any status. Can such people just not get into the statistics?

Denisenko: Yes, exactly. You can go to another country for a certain period, for example, on a grant, and not be among the permanent residents. Here again there is a problem of definition. A person considers himself a migrant, but the country does not consider him a migrant. Another category is people with two passports. They came to Russia, then something didn’t work out for them, they went back. They are not included in the statistics either.

After Bolotnaya Square, many also said that they had the feeling that everyone had left. And it was just, perhaps, those who left who had the opportunity – a residence permit or something else in another country. Then, by the way, there was a small surge, but literally for a year.

• Remember crying Putin? And rallies for a hundred thousand people in 20-degree frost? Ten years ago, the streets of Moscow became the scene of a real political struggle (it’s hard to believe now). That’s how it was

– Can the departure of people from Russia after February 24 be called a wave?

Florinskaya: Probably, if most of these people do not return. Because so many left to wait out the moment of panic. Still, most of them left in order to work remotely. How possible will this be? I think that soon it will not be very possible. Must watch.

In terms of the number [of those who left], yes, this is a lot in a month. [The level of emigration from Russia in the 1990s] has not yet been reached, but if the year continues as it began, then we will fit in perfectly and, perhaps, even overlap some years of the 1990s. But only if the departure will take place at the same speed as it is now – and, to be honest, I’m not sure about this. Simply because, in addition to desire and push factors, there are also the conditions of the host countries. It seems to me that now they have become very complicated for everyone.

Even if we don’t talk about wariness towards people with a Russian passport, but objectively, it’s difficult to leave: planes don’t fly, it’s impossible to get visas to many countries. At the same time, there are difficulties with obtaining offers, the inability to receive scholarships for education. After all, many of them studied with the support of scholarship funds. Now these opportunities are narrowing, because many scholarship funds will redistribute [funds] towards Ukrainian refugees. This is logical.

Who is leaving Russia. And who is coming

– Emigration can occur for various reasons – for example, economic, political, personal. In what case are we talking about forced emigration?

Denisenko: Forced emigration is when you are, shall we say, pushed out of the country. The war has begun – people are forced to leave. Ecological catastrophe – Chernobyl, floods, droughts – is also an example of forced emigration. Discrimination. One way or another, this is all that is connected with the concept of “refugee”.

There are clear criteria for identifying refugees and asylum seekers. If you take statistics, the contingent from Russia is not small. Traditionally, people from the North Caucasus, the Chechen diaspora, and sexual minorities fall into it.

– Is the mass exodus of people from Russia now a forced emigration?

Florinskaya: Of course. Although among those who left, there are people who planned to emigrate, but in the future, in calm conditions. They were also forced to flee, because they were afraid that the country would close, that they would announce mobilization, and so on.

When we talk about forced emigration, there is no time for reasons. People just think they are saving their lives. Gradually, when the direct danger has passed, it turns out that most of them left for economic reasons and will not return for them. Because they are well aware of what will happen to the Russian economy, that they will not be able to work, to maintain the standard of living that they had.

Some part – and quite a large part in this flow – will not return for political reasons. Because they are not ready to live in an unfree society. Moreover, they are afraid of direct criminal prosecution.

I think those who decide to leave permanently, rather than wait [abroad], will no longer choose the best offer. They will go at least somewhere where you can get settled and somehow survive these difficult times.

— How does emigration affect Russia in terms of human capital and economy?

Denisenko (answered a question before the start of the war, — approx. Meduza): You know, I want to say right away that it affects badly. We have an outflow of highly skilled and educated people, whom we identify with human capital. What is the contradiction here? There is a problem within the country – the mismatch of qualifications with the workplace. A person graduated, for example, from the Faculty of Engineering, and works as a manager in a store – this is also, to a certain extent, a loss of human capital. If we take this problem into account, then, probably, these losses are slightly reduced in terms of volume.

On the other hand, those who leave, to what extent could they be realized here [in Russia]? They probably cannot fully realize themselves, as they do there [abroad], in our country. If people, specialists leave and keep in touch with their homeland, be it money transfers, an influx of innovations, and so on, this is a normal process.

Florinskaya (answering a question after the start of the war, – approx. Meduza): For Russia, it’s bad. The flow of qualified emigrants, that is, people with higher education, will be higher this year than in previous years.

It seems to be all the same [insignificantly] in relation to our vast homeland, nevertheless it can affect. Because there is a mass departure of citizens, people of different specialties, but with higher education – journalists, IT specialists, scientists, doctors, and so on. This may well be damage, but it’s too early to talk about it. It can be assumed that this will be one of the most negative aspects of this forced emigration, even more than just the number [of people who left].

In this emigration, the proportion of people with higher education will change dramatically. It was already rather big – 40-50%, according to my estimates, but it will be 80-90%.

– Who comes to the place of people who left in Russia? Is the loss replenished at the expense of other segments of the population and migrants?

Denisenko: In the 1990s and 2000s, there was a replacement. A lot of highly qualified people came from the Union republics. Now there is no such replacement. Young people leave, the potential is lost to some extent. This is true loss.

Florinskaya: Whom to replace? We understood about journalists – [the authorities] do not need them. Highly qualified IT specialists, I think, will be problematic to replace. When the researchers start to leave, nothing can be done either. Doctors from the capital who left, as usual, will be replaced by doctors from the provinces. In the places of retired employees of large firms, I think, they will also be drawn from the regions. Who will remain in the regions, I do not know. Even 10 years ago, they said that Moscow is a transit point between the province and London. This is a joke, but this is how emigration always went: people first came to Moscow, and then from there they went further to foreign countries.

Most of the migration [to Russia] is still unskilled, so this is not the case [when migrants can replace the departed specialists]. The most talented and qualified from the CIS also prefer not to stay in Russia, but to leave for other countries. It used to be necessary to attract them, but then we turned up our noses. And now why should they go to a country under sanctions, if you can work in other countries? It is hard to imagine that someone will go here in these conditions.

WHAT WILL HAPPEN TO THE LABOR MARKET IN RUSSIA

• Are we going back to the 1990s? How many people will soon become unemployed? Well, at least the salaries will be paid? Or not?.. Answers labor market researcher Vladimir Gimpelson

— Are there already noticeable changes in relation to labor migrants who worked in Russia until recently? Do they continue to work or are they also leaving?

Florinskaya: There were no changes at the beginning of March. We launched a small pilot survey, just got the data. Some part says that yes, it is necessary to leave [from Russia], but so far there are very few of them. The rest say: “We have it even worse.”

I think that the influx [of labor migrants to Russia] will be less than before covid. And due to the fact that the opportunity to come was again difficult: tickets cost a lot of money, there are few flights. But those who are here will wait to leave. Maybe by the summer it will be so bad here that jobs will be cut, and this will hit the migrants. But so far this is not happening.

– In general, the country should be concerned about emigration? How much attention should the authorities pay to it? Trying to prevent?

Denisenko: Naturally, attention should be paid to emigration. Why? Because emigration is a strong social and economic indicator. There is an expression: “People vote with their feet.” It is true for all countries. If the flow [of emigration] increases, it means that something is wrong in the state. When scientists leave, it means that something is wrong in the organization of science. Doctors are leaving – something is wrong in the healthcare organization. Graduate students leave – the same thing. Let’s go electricians – something is wrong here. This needs to be analyzed and taken into account.

Government policy should be open to those who leave. There should be no restrictions or obstacles. This evil practice does not lead to anything good. Take the same Soviet Union. There were defectors – Nureyev, Baryshnikov and so on. These are irreparable losses: we did not see Baryshnikov on stage, we did not see Nureyev, but they would have come if everything was normal.

How emigrants live and why they sometimes return to their homeland

Do you study people who have left? How often do those who leave manage to assimilate and begin to associate themselves with a new country?

Denisenko (answered a question before the start of the war, – approx. Meduza): I can express the opinions of my colleagues. Andrey Korobkov, a professor at the University of Tennessee, deals with the Russian-American topic and specifically with those [Russians] who live there [in the US]. Among them, the tendency to assimilate is very strong. If the Greeks are united by religion, the Germans by the historical past, then ours, who left in the 1990s and 2000s, tried to assimilate and dissolve as much as possible. Do you even know what it was? In limiting communication with compatriots. It was one of the indicators. Like now? It seems to me that this trend continues.

In European countries, for example in Germany, the situation is different: there are many Russian speakers there. These are not highly qualified specialists – once – but former villagers, Russian Germans who honor traditions. Many keep in touch.

Secondly, distance also plays a big role here: Germany is close to Russia. Many maintain very close relations with the country, so assimilation is slower. There is also the specifics of the country: Germany is smaller [than the US], there are regions of compact residence, there are many former Soviet military men left.

In France and Italy, the problem of assimilation is posed differently. We have Italian migration – 80% of women. French – 70%. There are many “marriage” migrants, that is, those who marry.

Great Britain, it seems to me, is following the same path as the States: after all, people are trying to at least make their children “English”. The migrants themselves do not break the connection with the country, it is difficult for them to do this: many of them still have business, real estate, friends in Russia. But their children are absolutely not interested in their country, and if they are interested, then it is weak.

– According to my observations, many of those who left Russia from 2020 to 2021 categorically refuse to call themselves emigrants, although they fit this definition. How common is this?

Denisenko: An emigrant is a migrant, a person has left for permanent residence (permanent residence, — approx. Meduza), roughly speaking. Vladimir Ilyich Lenin did not consider himself an emigrant, although he wandered around Europe for a long time – but he hoped to return. Here, apparently, they want to emphasize that under changed conditions they will return to the country.

It seems to me that this is the only explanation here: they retain their identity while abroad, do not try to blur or hide it in any way, but emphasize: “I am Russian/Ukrainian/Georgian, I will definitely return to my homeland, maybe 20 years later, but still.”

It’s like in their time with Nansen passports. Most of the countries where the white emigration was located were allowed to accept their citizenship. But [some] remained with Nansen passports. They did not consider themselves emigrants in white emigration and hoped that they would return.

– Most of those who left find what they want? Are there any studies on the level of happiness among those who have left?

Denisenko: Research on the level of happiness is being carried out. But I would give other parameters as the level of happiness.

Israel is a good country to study the consequences of migration for us. Because in Israel statistics on migrants from the Soviet Union are kept separately. What do we see from these statistics? Since the 1990s, Jews who have emigrated to Israel have begun to live longer. That is, their life expectancy is much higher than that of those Jews who are here [in Russia]. They have increased their birth rate. And in the Soviet Union and Russia, Jews are the group with the lowest birth rate.

There are no such statistics in the States, but there are other statistics – for example, the same incidence in older people. I will never forget when I was standing in line for tickets to the Metropolitan Opera in New York, two women were standing behind me. They spoke Russian, and we got to know them. These women were emigrants from Leningrad. At some point they cried. Do you know why? They say: “You know, we are so uncomfortable. We moved here and we are happy here. We are treated, we receive a large allowance, we can go to the Metropolitan, but our friends and colleagues who remained in Leningrad are deprived of all this. Some of them have already died while we are here, although they are our peers.”

Such indicators are very revealing. Career, income, education, employment are also indicators. We see that in the States and Canada, the Russians eventually occupy good positions. Europe is the same.

— How often does re-emigration occur? When and why do people usually return?

Florinskaya: Re-emigration took place, but how often quantitatively it is very difficult to estimate. The more international business developed in the country, the more international companies there were, where those who received a Western education were in demand, the more [young specialists] returned. The more international research, international level laboratories, the more researchers returned.

Once it all collapses, there is nowhere to go back. Plus, a certain level of salaries is also important.

Will many of this wave return?

Florinskaya: People who are tied to the Russian labor market, who will not be able to find a job [abroad], will return simply because they “eat up” the reserves, and there will be no other work for them. Not everyone will be able to work remotely for Russia. I know some people working for Russian companies who have already been forced to return. There are companies that have banned working from foreign servers. There are students who were not allowed to take sessions online. Therefore, even if 150 thousand left, this does not mean that some of them did not return.

Again, this does not mean that people now, seeing this whole situation, are not preparing their departure, but just not in such panicky circumstances. If earlier, before the COVID-19 period, 100-120 thousand people left Russia a year, now, it is quite possible that the numbers will reach 250 thousand or 300 thousand. It will depend on the ability to cross the border, the number of flights and the ability to catch on somewhere in other countries.

[Before] people told us in in-depth interviews: “If I am in demand, find a job, then I do not rule out a return for myself.” But as economic and political freedom disappears in the country, the circle of those who can return is potentially shrinking. Now it has shrunk even more.

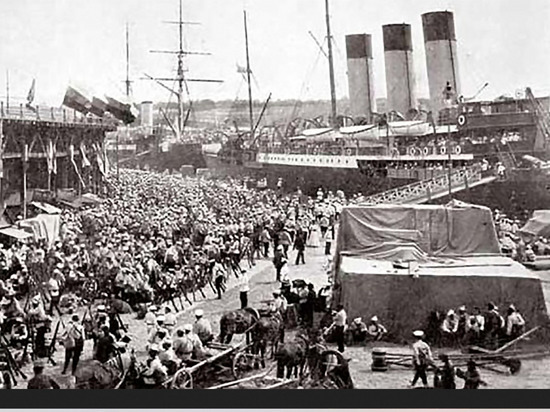

Photo: Evacuation from Crimea. 1920